‘From the comic to the sacred': Memorial Day and U.S. military rugby

This weekend brings MLR tributes to the troops including an Army v Navy game in Seattle. I'll be thinking again about West Point and the team I came to know so well

In Seattle on Friday, the Seawolves will face the Houston Sabercats in a Major League Rugby game that will have much to say about who makes the end-of-season play-offs. As Friday is also the start of the Memorial Day weekend, the Seawolves are making it a Salute to Service Night. In a curtain-raiser, 15 men of the U.S. Army will face 15 from the Navy.

An organizer, Deane Shepherd explained: “This Friday night will be the annual Pacific Northwest Army-Navy Rugby game.

“What started from a bar discussion between a coach from Tacoma, a team made up of a lot soldiers from Fort Lewis, a coach from Bangor, [and] a team made up primarily of sailors from Naval Sub Base Bangor and the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard, about playing an annual Army-Navy game, has continued for over two decades. It continues to grow.”

Shepherd is of course not alone in organizing and promoting the game, pointing to a “lion’s share” of work done by Nick Punimata from Fort Lewis and Kevin Flynn from the Seattle Rugby Club. Nor will Seattle be alone in staging a military themed event. On Saturday, on the other side of the country, the double-champion New England Free Jacks host Old Glory DC in Quincy, Massachusetts, as part of their own Tribute to the Troops.

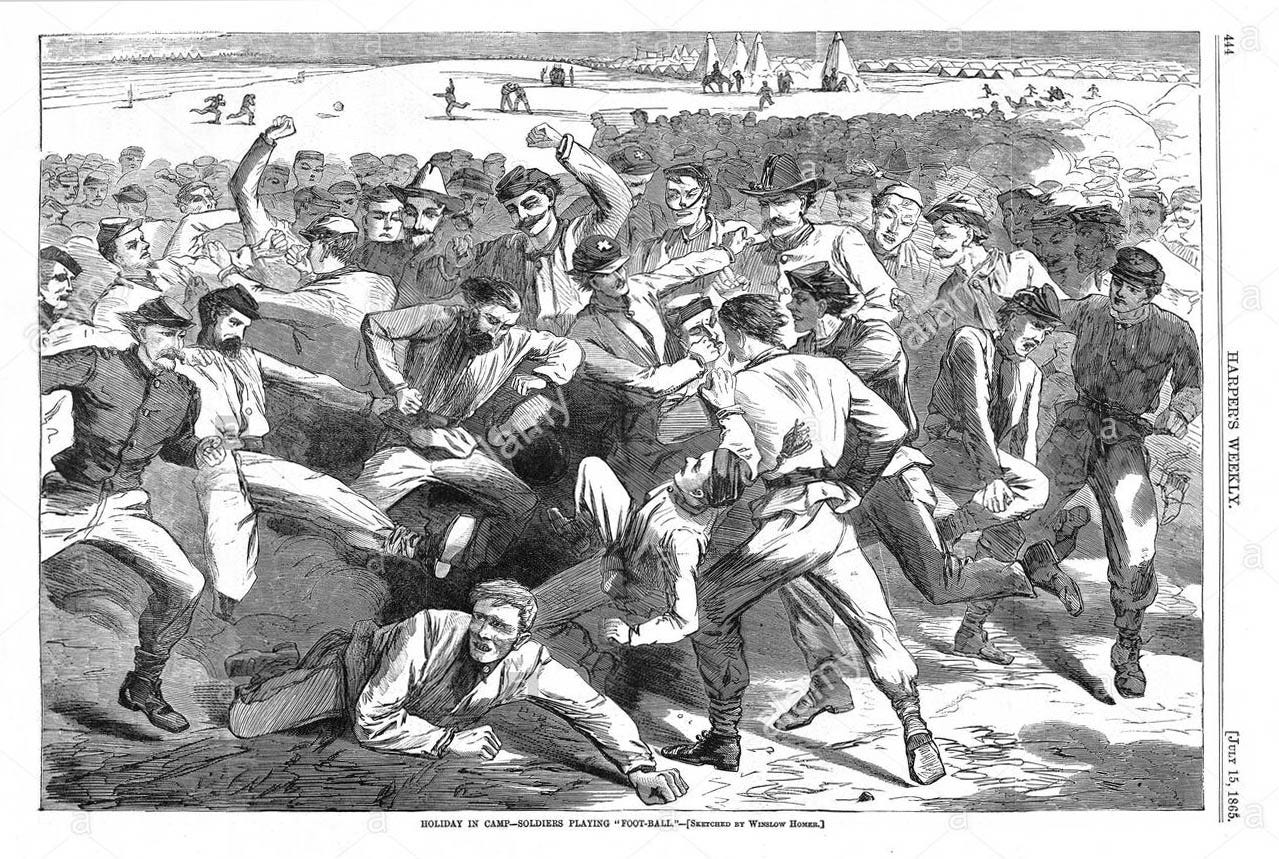

None of this should be surprising. Around the world, rugby and the military have always gone together. After all, as George Orwell wrote, “serious sport … is war minus the shooting,” and as I have written, rugby is a more martial sport than most, with its “forward battles and blitz defenses and high kicks known as bombs.”

I wrote that at the start of the eight-year process that ended with publication of a book about rugby at West Point and the war in Iraq. Last week, I was supposed to sign copies at Old Glory’s own military night, at George Mason University in Virginia, only for illness to intervene. Never mind.

Thanks to the book, I’ve met many good people, the Army and Navy vets I played with out in Virginia prominent among them. So is Dan Vallone. A 2007 West Point grad, he’s now the author of Army 250, a newsletter about “how the U.S. Army has shaped American culture and society”, launched to mark the Army's 250th birthday this June. A while ago, Dan interviewed me. More recently, he wrote about the Gettysburg Film Festival, in Pennsylvania, at the site of the Civil War battle.

In one event, John Orloff, who wrote two episodes of Band of Brothers for HBO, described the sense of responsibility he felt when telling the story of Easy Company. As Dan noted, Orloff also talked about how that story largely told itself, because “if you need to juice up a story about men who jump from airplanes into gunfire and then fight through some of the worst conflicts in the largest war humanity has ever known, then ‘you are not a fucking writer.’”

As Dan put it, Orloff’s remarks “ranged from the comic to the sacred.” To me, that line captured a major way that rugby and military culture collide: through humor.

Dan might’ve written that Orloff ranged “from the sacred to the profane.” It would have been equally fitting. In my book, I tried to capture more than a bit of rugby and military profanity, leading to an imperishable reader’s note from my mum: “Page 26: are you sure about ‘useless cunt’?”

Mum’s in her 80s, a retired English teacher, but it wasn’t that she was shocked. After all, her dad was a miner and her brother a copper, she studied DH Lawrence, and she raised three sons who played rugby three times a week. There isn’t a swearword Mum hasn’t heard, or said with Withnailian relish, or chased down etymological pathways through Shakespeare and back to wherever.

But if her note raises a laugh, it might also help explain why Dan’s line about the comic and the sacred turned my mind to rugby.

There is rugby humor, and there is rugby humor. I’m not talking here about cheap T-shirts that say “Give Blood, Play Rugby” or “Hookers Do It with Odd-Shaped Balls”; or predictable tales of the sort old players tell about the communal showers; or even rugby songs, some of them lewd but fiendishly clever, some lewd and not very clever, many merely appalling. I’m talking about the existential humor of rugby, as contained in stories or jokes born of the fact that playing rugby is a dangerous and silly thing to do, but we do it anyway, resulting in the telling of stories that, like stories about the military, can achieve a sort of brutal grace.

When Dan interviewed me, he asked: “When you speak about the book, what is it that resonates the most with audiences?” I answered: “There is a resounding sadness to the book, leavened with doses of rugby humor. Audiences understand that. Sometimes that humor becomes pitch black, but audiences get that too.”

Consider one story told by Pete Chacon, a winger in the West Point team of 2002 who became an officer in the 101st Airborne, the division of which Easy Company was part. Pete’s story is a military story but the rugby spirit shines through.

In December 2003, in Mosul in northern Iraq, Pete’s Humvee hit an IED. The blast knocked Pete unconscious. Coming round, he found he had “dust and blood all over” and looked “like a porcupine,” shrapnel studding his face. Then he found that while he was out, his men had tried to carry out they plan they’d formed for such an event. The plan was to arrest everyone within 50ft of the blast. The blast was within 50ft of the only Catholic church in the Muslim city. Worshipers rushed to help. The Americans arrested them all.

"And they're like, 'Dude. Sign of the cross.' They're pointing. So I turn to my guys. I'm like, ‘I'm knocked unconscious for 15 seconds and you arrest the only fucking Christians in the entire fucking city. These guys didn't plant bombs. They’re hoping we take over. The one Catholic church in the entire fucking country, and you arrested everybody?’ And my guys say, ‘Well, that was our plan. We were gonna arrest everybody we saw.’

"… I was like, 'This is insane. Somewhere else in the 50ft radius, there's a guy running around who just detonated this thing. They're like, 'Oh, yeah. We didn't think of that.’ I'm like, ‘Dudes, I get knocked unconscious for 15 seconds and this is what happens.' It was very, very funny."

As told by Pete, it really is funny. And appalling. And that is entirely appropriate. It’s a war story, and they’re often funny, and appalling, just like stories about a particular rugby game or a particular night on tour, told for years, repeating and mutating.

Pete has rugby stories too. For example, about how he got his nickname:

He's dark and his surname isn't Irish like Hurley or German like Blind or English like Radcliffe or Phillips. At West Point, inevitably, his nickname was "Mexican Pete." In Massachusetts, on Matt's boat on the way to lunch at Marblehead, he worked his way to the stern.

"Hey, Dave," he shouted to his big buddy, the No8. "Guess what? You're more Mexican than me!"

True. The Chacons are French-Portuguese. The Littles, from San Diego, have their Anglo name but via Dave's mother they also have a Mexican line.

Laughter. Beer. The reverent irreverence of rugby. The old every-body-gets-it shit, close to the line, not over it. This time.

That lunch at Marblehead, on the Massachusetts coast, was a major moment in my journey to understanding that West Point rugby team, their dynamics and their bond. At the table, Pete re-told the story of their hooker, Jim Gurbisz, about how he kept joking as he lay dying in Baghdad, victim of another roadside bomb. The book deals with that story, its various iterations and mutations. It’s the toughest thing I’ve ever written, but also, I hope, the most necessary and most true.

In the book, I mention that in Marblehead, after Pete told the story about Jim, “someone ordered up a round of Irish Car Bombs (stout, whiskey, Irish cream), and, delighting in the grim irony, the Brothers raised a toast to Gurbisz.”

It was funny. Honest. Pure rugby and military humor, comic and sacred both.

Another such moment didn’t make the book. It happened on Matt Blind’s boat, on the way back to Cohasset, where the players staged a reunion, two days of beer and laughter.

Out in Massachusetts Bay, halfway across the mouth of Boston Harbor, Matt stopped the boat so passengers could piss off the side. A few jumped in for a swim. Most stayed aboard. After a minute or two, one of the men in the water looked up at his captain and voiced the question we’d all been thinking.

“Hey, Blinder. You get sharks here?”

“Yeah. Great whites. Big ones.”

In swearing, rushing seconds, the boat was fully crewed. Matt started up the engine, set a course for home. Everyone was laughing.

Further reading:

From Heaven to Hell, Dan Vallone, Army 250

Rugby: the Soldier-Making Game, Ruben Stewart, War on the Rocks

‘They’re not quite right in rugby’: how West Point made one band of brothers, MP, The Guardian

A Very, Very Dirty Word, Christopher Hitchens, Slate

Sacred and profane. Worthwhile combo to live by and for. Enjoy yourself while doing the hard stuff that moves the needle. Great post